I miss baseball. I miss it a lot. So I’ve turned to new ways to get a “fix” on the game. One of the things I’ve started doing is looking at MLB Network. They are, among other things, running a lot of old games during the day (and occasionally in prime time). Most of these are fairly recent (1980s through 2019), but some go back into the 1960s (game 7 of the 1965 World Series) and some even further. I finally got to watch the complete (sans the first inning) game 5 of the 1956 World Series (Larsen’s perfect game). I’d gotten home from school in time to see the last one or two innings on the television and found out from my grandfather what a “perfect game” was (I’d never heard the term).

The oldest games I’ve run across are games 6 and 7 of the 1952 World Series (Yankees over Dodgers). I’d never seen either, even I’m not old enough to remember them (I was not yet in school when they were played) and we’d only had a radio at the time anyway, so it was interesting to watch them. In doing so, I noticed a number of changes in the way baseball was played in the 1950s from how it’s played today. In no particular order:

1. I noted how high the catcher sat up. Modern catchers are low in the strike zone, but the 1952 catchers (Berra and Campanella) were setting up much higher, especially Campy. Maybe it was the pillow mitt, but it was noticeable.

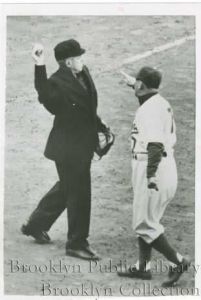

2. The umpires still wore suits and the small billed cap that has now disappeared (look at the picture of an old umpire shown above to see what I mean). And the home plate umpire still had the outside pillow protector. It really looks odd today.

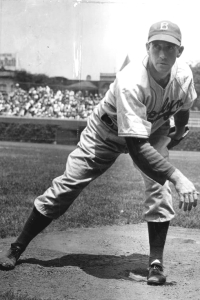

3. Pitchers seem to pitch longer. In game 6 of 1952, the Dodgers Billy Loes was in trouble late and stayed in to face what would eventually be the critical at bats that cost Brooklyn the game. In today’s game, Loes would have never gotten to the eighth inning.

4. The male fans wore suits and ties and the announcer had to tell them not to hang their jackets over the railing in the outfield. Don’t see that much today (and I’d never heard the announcement about the jackets before).

5. There didn’t seem to be as much stepping out of the batters box as today. Now they’d edited the game for time purposes, so they may have cut out a lot of that, but it certainly seemed less.

6. The main camera was purchased high behind home plate, making it easy to see the pitcher, but difficult to make out the batter’s stance or where the ball hit the mitt when pitched. The center field camera is much better.

7. Not a helmet in sight.

8. You see many more of the outfielders going down on one knee to field a ground ball hit to them. Don’t see that technique much anymore.

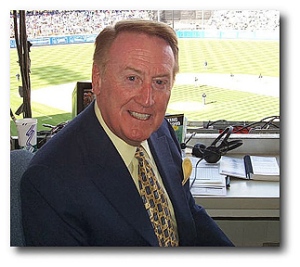

9. And it was wonderful to hear Mel Allen and Red Barber call the game (they worked together). If I could put together a Mount Rushmore of play-by-play men, they’d both be there, probably along with Vin Scully and Jack Buck (sorry, Diz, but you’re not in the category).

If you get a chance to take in one of the games, especially one of the 1950s games, do so. Odds are you’ve never seen it and you should. Enjoy.